This article is jointly authored by Raymond McDougall, David K. Joyce and Ian Nicklin. Except as otherwise credited, all photographs are R. McDougall photos.

Just north of Lake Superior, the Thunder Bay District of Ontario is world famous for its distinctive, ancient amethyst crystals. Thunder Bay amethyst has been known since the 19th century, and is remarkable for its variety – it occurs in all shades of purple from pale to deep, from warm to cool hues, it is often further coloured by inclusions (most often red, due to included hematite) and once in a while phantoms are also found. It is a long journey to the amethyst mines of the Thunder Bay District, and hopefully this article will bring this beautiful region, its history, geology, mines and collecting experience a bit closer!

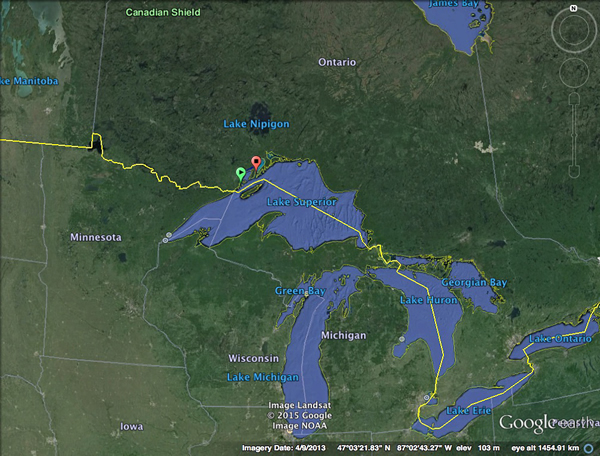

Location

The Thunder Bay District is located along the northern shore of Lake Superior. The Thunder Bay District is a formal subdivision of the Province of Ontario comprising over 103,000 square km. The amethyst-producing region, within the Thunder Bay District, is located in an area approximately 60 km northeast of the city of Thunder Bay. Just to give you a sense of how long a drive it is to reach the amethyst area from major international centres, it is over 1200 km from Toronto and over 1000 km from Chicago. (Closer large cities are still a surprisingly long way from Thunder Bay: Milwaukee over 900 km, Winnipeg over 700 km and Minneapolis-St.Paul approx. 550 km). Flights from Toronto are frequent, but commercial air travel is not the most convenient when transporting major collecting gear or any decent amount of specimen material.

North of Superior

The land north of Lake Superior is rugged – it is stunning, wild country. It is one of the most beautiful regions in Canada, but because it is relatively remote from major population centres, it is not as well-known or as frequented as some of our more famous scenic locations. It is a land of the Canadian Shield, with exposed Precambrian rock, lakes and evergreen forests.

The distant hills are often quite rounded thanks to the glaciers, and in many places, the shoreline rock has been shaped into smooth forms, first by the glaciers, and since the end of the last Ice Age, by the unrelenting waves, ice rafts and deep frost

Inland from the shoreline, signs of the last glaciation are still readily apparent, with rock faces worn smooth, and interesting features like the deep, dark, round pools known as kettles, created by powerful glacial runoff, carrying rocks as abrasive agents. The most recent glaciers receded from the area approximately 10,000 years ago.

Even beyond the glaciers and away from the shoreline of Lake Superior, this region is constantly being visibly reshaped – by heavy storms, and often just by water as it makes its way from higher land down to Lake Superior.

Speaking of storms, Thunder Bay is named for the sound of the thunderstorms as they roll through. Severe thunderstorms are common throughout Ontario in the summer months, but they are just awesome in Thunder Bay, where the thunder booms around the bay and echoes off the surrounding landforms. (It is an amazing experience. Ideally not experienced in a tent.)

The Thunder Bay District is home to lots of wildlife, including large mammals such as moose, timberwolves and black bears.

From Early People to Modern Times

After the glaciers retreated, the first people moved in to inhabit the lands along the north shore of Lake Superior, approximately 10,000 years ago. Several peoples have lived in this region since that time, the Plano, the Shield Archaic, the Laurel and the Terminal Woodland peoples, and the Anishinaabe (including the Ojibwe, or Chippewa). They have hunted, fished, gathered berries and even mined native copper – and they have been active traders. Early inhabitants used canoes for water transportation – first, canoes were carved out of large tree trunks, and later canoes were made using lighter wooden frames covered by birch bark and assembled using a glue made largely from tree resins (combined with animal fat and soot).

Today, there are few tangible signs of most of these early peoples. In some places, small stone pits and piles of stone are evident, and artifacts have assisted researchers to better understand the past of the area. Painted red ochre pictographs are seen on the Lake Superior shoreline cliffs – these are comparatively recent, estimated to be 200-400 years old.

With the arrival of the first French explorers in the mid-17th century and the opening up of trade by the British and the Hudson’s Bay Company, life around Lake Superior began to change. Through trade, the French and the British engaged with the Ojibwe people. As the British continued to explore and develop these interior regions during the nineteenth century, prospecting and mining followed.

In the beginning, what is now the city of Thunder Bay was comprised of two separate settlements/towns (it was not until 1970 that they amalgamated as Thunder Bay). The first was Fort William, which was established in 1803 by the North West Company as a trading post for furs and other goods. After the merger of North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1821, the importance of Fort William as a trading post diminished, although the settlement continued on and became a town.

In the latter half of the 19th-century, a second settlement, initially named Prince Arthur’s Landing, was founded nearby in connection with the Government of Canada’s post-confederation efforts to extend the railway from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific. Soon renamed Port Arthur, it was was initially supported by local silver mining. As the silver mining declined, the era of railway development was on the rise, and both Port Arthur and Fort William were to become important Canadian railway towns. Port Arthur was the key rail terminal for Western Canadian wheat, which was then loaded onto ships and transported through the Great Lakes.

Once the first railway across the north of Lake Superior was completed in 1885, trains were the major means of land transportation across the region for the next 75 years.

These same Northern Ontario railways are still fundamental Canadian transportation corridors today, linking Central and Western Canada. The echo of trains in the distance day and night is an evocative sound of this part of the country.

Because the land is so rugged, with steep hills and river gorges, the last section of the Trans-Canada Highway linking Thunder Bay with Sault Ste. Marie (at the eastern end of Lake Superior) took decades to complete and was only finally opened in 1960. Today the Trans-Canada Highway in this region runs like a ribbon through hundreds of kilometers of rocky forest, sometimes relatively close to the lakeshore, and sometimes much further north, where construction was more feasible.

Ancient Geology

The land north of Lake Superior is part of the Canadian Shield, and includes ancient rock types dating back to 2.7 billion years old. The landforms and rocks evidence mountains and volcanoes that have come and gone, and massive geological events including regional structural metamorphism, folding and major faulting.

The amethyst deposits of the Thunder Bay District are associated with the rocks of the Osler Group, formed during a late Precambrian stage of volcanism and faulting, from 1.2 to 0.9 billion years ago. In general, the amethyst deposits are in or near the granitic rocks, in proximity to the contacts between the rocks of the Osler and Sibley Groups. The faulting and related fracturing of these rocks during the late precambrian allowed for the intrusion of the fluids which ultimately led to the deposition of the amethyst crystals. These fluids precipitated the amethyst (and also silver, lead and zinc-bearing minerals at the localities where they occur) onto the walls of the fractures, creating crystal-lined veins and cavities. The faulting and fracturing – and therefore the nature and occurrence of ameythst-bearing veins – differs somewhat from locality to locality within the Thunder Bay District. Some brecciated zones are characterized by large numbers of relatively parallel small veinlets, while in other places much larger fractures are hosted by much more competent rock. The size of individual amethyst crystal-bearing vugs and cavities can vary significantly – they can be as small as 2 cm and a cavity 15 x 3 x 2.4 metres has been excavated. The vugs and cavities within a vein or berated zone are often interconnected with one another.

History of Thunder Bay District Amethyst Discoveries

Silver was discovered in the Thunder Bay District in the mid-19th century and soon silver mines were operating. Amethyst was found in these mines, and was described by W.E. Logan (founder of the Geological Survey of Canada, and namesake of weloganite) in a report in 1846. By 1887, G.F. Kunz was reporting a thriving trade and exports of amethyst from the Thunder Bay District for tourists and for building materials. However, by the early 20th century, two factors led to the decline of the Thunder Bay District amethyst trade: the silver mines began to close and large amounts of high-grade Brazilian amethyst began to appear on the market.

For mineral collectors, the most important amethyst discoveries were yet to come. In 1955, amethyst crystals were discovered northeast of Port Arthur in McTavish Township, but it was the discovery by Rudy Hartviksen in 1967 at Loon Lake (also in McTavish Twp.) that began the modern era of fine amethyst production from the Thunder Bay District. The deposit found in 1967 was to become the Thunder Bay Amethyst Mine, the largest commercial amethyst mine in the region. It has operated continuously since that time and is now named the Amethyst Mine Panorama. Many other localities in the Thunder Bay District have been operated since 1967, and perhaps the most prolific for producing fine, top-quality collector specimens has been the Diamond Willow Mine.

The Diamond Willow Mine

The Diamond Willow Mine works a vein in McTavish Township, in the Thunder Bay District, located on a claim block at the northern end of Pearl Lake. It was named by its owner, Gunnard Noyes, after the type of willow tree that grows at the site of the mine and is highly prized by wood carvers. From the late 1970s and for over 30 years, a section of the vein was leased and worked in the summers by the father-son team of David and Ian Nicklin. They collected with great care and produced some of the finest quality amethyst to have ever come from the Thunder Bay District. The Diamond Willow vein was also regularly worked by Gunnard Noyes, his sons Doug and Clark, and later his daughter Francis.

To give a small insight into what really lies behind the excellent amethysts mined during that time at the Diamond Willow Mine, the following account is written by Ian, together with a few photographs from mining in those days.

Amethyst Mining at the Diamond Willow Mine

My father, Dave Nicklin, and I first met Gunnar on the suggestion of the Ontario Geological Survey regional geologist in Thunder Bay 42 years ago, while on a summer rock collecting trip. Gunnar had worked in the mines at Sudbury for many years and had retired to the small railway stop town of Pearl, approximately 60 km northeast of Thunder Bay. He was a great source of stories and a remarkably generous man. Knowing of the amethyst riches in the region, he staked his several claims just north of the hamlet of Pearl but when we first met him they were not developed to any extent. The claims were only accessible by a narrow twisting trail or by canoe, up Pearl Lake.

On our first visit, my father and I canoed Gunnar’s ancient but still functional Atlas Copco Cobra plugger drill up the length of the lake and met him at the trailhead. I was 16 at the time. Although I was quite strong for my age, I clearly recall complaining about the weight of the drill as I struggled through the bush with it. Gunnar, a man well into 60s at this point, laughed at my complaints, grabbed the drill from me and hoisted it onto his shoulder with no fuss. (Anyone with any familiarity with Cobras knows what that takes and just how uncomfortable it is.) I think he was enjoying showing up the young pup.

We eventually reached a small clearing on an outcrop where there was evident signs of blasting and some amethystine rubble. This was the beginning of the Diamond Willow Mine. Gunnar drilled some holes with the plugger and prepared to put off some shots. He had stuffed some sticks of Forcite 40 into his pockets before heading up the trail. This was the first time we had seen blasting up close and as with most things associated with Gunnar it was memorable. He had some pre-cut fuse and a few blasting caps which had to be crimped onto the fuse with special plyers. In later years, we would use electric caps but these were still early days. He set the charges, lit the fuse (it would burn for about 30 seconds) and told us to find cover … which we did.

As we walked away – never run from an impending blast – to find shelter (with Gunnar yelling “Fire!”, the signal for anyone who might be nearby that an explosion was imminent) I became aware just how long 30 seconds can be. The anticipation of the bang made the seconds interminable. But off they went and I can still see the smoke slowly wafting through the trees and the smell of cordite in the air as we made our way back. And there lay our first amethyst specimens, which I still have to this day. We collected about 100 pounds or so of specimens and packed them into the canoe for the trip back. This was the beginning of a 42-year-long relationship, first with Gunnar and later with his sons.

My father was a teacher and so he had the summers off. While I was in school, we would return to the Diamond Willow every year, collecting for several weeks. Later my father and mother bought a trailer in a nearby camp and spent the summers there – I would join them as time allowed.

We learned how to quarry, drill and blast. Although we used feather-and-wedge method of rock removal as much as possible (to minimize chances of damage), blasting was normally mandatory.

We typically used Forcite 40, which we found to be a good general purpose explosive and usually loaded the holes lightly so as to crack the rock but not throw it to minimize damage to the pockets. It might take a full day of drilling to lay out a blast and I clearly remember not being able to open my hands fully without pain after a day on the plugger.

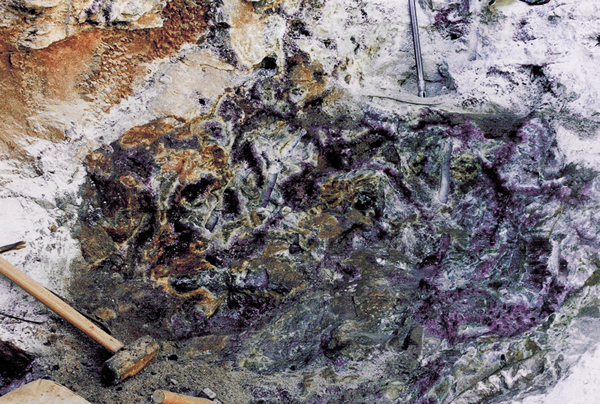

The amethyst at the Diamond Willow Mine had a complex history of formation, with the crystals first forming tight to the walls of the pockets and then later, probably due to more geologic activity along the fractured fault systems the plates of crystals collapsed into a jumbled mass. At some later time these pockets became filled with a stiff red clay. This history of formation is something of a mixed blessing. If the pockets had not collapsed the crystalline plates would have to be cut or otherwise chiselled off the walls making recovery much more difficult. But of course, because they are collapsed, the plates suffered nearly ubiquitous damage. (Another “fun” aspect of working in the clay filled pockets is that the clay is typically riddled with tiny, razor-sharp quartz shards… after a few weeks of that, your hands are in rough shape…)

Although we have not been back to the Diamond Willow for many years now, today it is still in production.

- Ian Nicklin

Thunder Bay Amethyst

Crystallized quartz in the Thunder Bay District is found in vugs and cavities of varying sizes, from 2 cm across to a cavity large enough that you can crawl in. Donald Elliott (1982) describes one pocket that was 15 x 3 x 2.4 metres in size (references are listed at the end of this post). Amethyst crystals from the Thunder Bay District are most commonly 1-2 cm in size, but larger crystals are also occasionally found. Rarely, very large crystals have been found – a crystal 61 cm across is reported in Elliott (1982).

Thunder Bay quartz crystals occur in many colours and shades, from colourless to smoky quartz, and the variety amethyst occurs in crystals from delicate pale lilac to a deep purple that can approach black. The lustre of Thunder Bay amethyst ranges significantly from the best of the brilliant, lustrous crystals at the Diamond Willow Mine (some of which look perpetually wet (!)) to crystals that are not bright and can even be fairly dull in lustre.

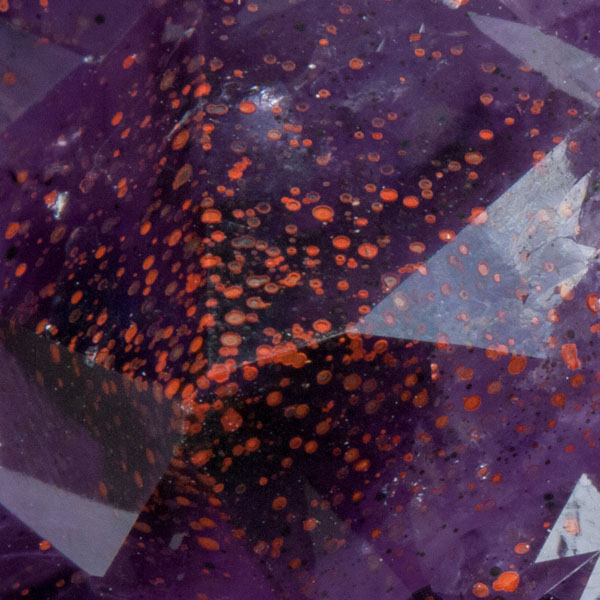

One of the most beautiful and distinctive characteristics of many Thunder Bay amethysts is the inclusion of red hematite (microscopic disks/spherules within the amethyst). The inclusion of red highlights, red zones, and even completely red amethyst crystals are all a classic look for Thunder Bay specimens.

The crystal morphology of Thunder Bay amethyst is basic, as most crystals exhibit only well-developed pyramidal faces. Prism faces are uncommon, and doubly-terminated crystals are rare.

Some specimens are entirely red, and some show distinct zoning – the crystal surfaces are red and amethyst is evident as an earlier phase growth.

One of the authors has always thought the completely red ones look like clusters of jasper crystals, if only jasper crystals existed. (Neither Ray nor Ian has ever contemplated the existence of jasper crystals – both agree that’s a great description of the intense tone of red.) Certain of the completely red crystals have been found to be comprised internally of zoned ametrine, underneath the red outer layer.

The best of the amethyst specimens mined by David and Ian Nicklin at the Diamond Willow Mine are remarkable, in part for their brilliant lustre and exceptional condition.

Labelling Thunder Bay Amethyst

The history of the amethyst discoveries and production of the past is helpful in understanding locality information, particularly for older specimens. it is also instructive for all specimens where the labelling has been vague. It is so common to see mineral specimen labels with “Thunder Bay, Ontario”, and no further information. Although “Thunder Bay amethyst” has actually occasionally been found right inside the city limits, the city of Thunder Bay is not the source of the Thunder Bay amethyst specimens on the contemporary mineral market. Similarly, it would be a feat today to obtain an amethyst specimen excavated in the silver mines of the area before the early 20th century. Unless a specimen is actually known to date to the early 20th century or earlier, specimens labelled “Thunder Bay, Ontario” (or, one sometimes sees “Port Arthur, Ontario” on pre-1970 specimens) are most likely from any of a handful of producing mines and properties – or possibly even any of a rather large number of prospects and additional known deposits – most of which are in McTavish Township, in an area beginning about 50 km northeast of the city of Thunder Bay. Absent specific locality information, the use of only “Thunder Bay” on a label should be considered to refer to the Thunder Bay District.

Thunder Bay Amethyst – Today and Future

Thunder Bay amethyst is among North America’s finest and is known by collectors around the world. These amethysts are contemporary classics for mineral collectors. Because the amethyst-lined vugs of any size naturally have collapsed during their history before anyone has found or collected their contents, excellent quality specimens will always be uncommon, hard to obtain and highly prized.

Amethyst has been found at many localities over a considerable area within the Thunder Bay District (localities up to 200 km apart) and mining continues today at a few properties. As Frank Melanson (2012) points out, thanks to our winters it is a short mining season, and thanks to the rugged terrain, access and access cost is always an issue, so it is difficult to mine Ontario amethyst profitably. And yet, the lure of the amethyst continues to inspire ongoing efforts, despite the economic hardships (and not to mention the black flies!). In Frank’s words, “for many, keeping the mines open was a labour of love.”

It is possible to personally collect amethyst in the Thunder Bay District, primarily on a fee-collecting basis, and also at other prospects and exposures. All of the authors have collected amethyst crystals in the Thunder Bay District. Most individual collecting is typically on the dumps, notably at the Amethyst Mine Panorama, but it is difficult to find collector-quality fine mineral specimens on the dumps. Other collecting is just a bit more involved, as Ian’s description conveys!

When amethyst was first encountered in the early silver mines of the nineteenth century, no-one would have foreseen the story of Thunder Bay amethyst as it has unfolded. Thanks to the later vision and pioneering efforts of Gunnar Noyes, Rudy Hartviksen and others, those first finds of amethyst would lead to the discovery of significant amethyst deposits and the preservation of spectacular amethyst specimens that now reside in museums and collections all over the world. It is unclear how many Thunder Bay amethyst mining ventures will be able to continue in the future, but it is likely that fine specimens will continue to be found, in very small numbers, relative to the amount mined. It is also likely that the best amethysts mined by David and Ian Nicklin will, for a very long time, be considered among the finest quality amethysts ever collected in the Thunder Bay District.

Many, different, beautiful amethyst specimens from this locality are available on both McDougall Minerals and David K. Joyce’s websites; click, here, on David K. Joyce or McDougall Minerals links to go directly to them.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the Noyes family for their kindness and generosity, and for enabling the development of their deposit such that Diamond Willow Mine amethyst crystals will be enjoyed in collections worldwide for generations to come.

Thanks also to Tory Tronrud and the Thunder Bay Historical Museum Society for kind assistance and permission to share the Fort William mountain train photograph in this article.

References

Elliott, D.G. (1982) “Amethyst from the Thunder Bay region, Ontario” The Mineralogical Record. March-April 1982, vol. 13, no. 2.

Melanson, F. (2012) “Purple Rain: Thunder Bay Amethyst” No. 16: Amethyst, Uncommon Vintage. Gilg, H.A., Liebetrau, S., Staebler, G.A. and Wilson, T., eds. Lithographie, Ltd.

Vos, M.A. (1976) Amethyst Deposits of Ontario Ontario Division of Mines – Ministry of Natural Resources, Geological Guidebook No. 5.